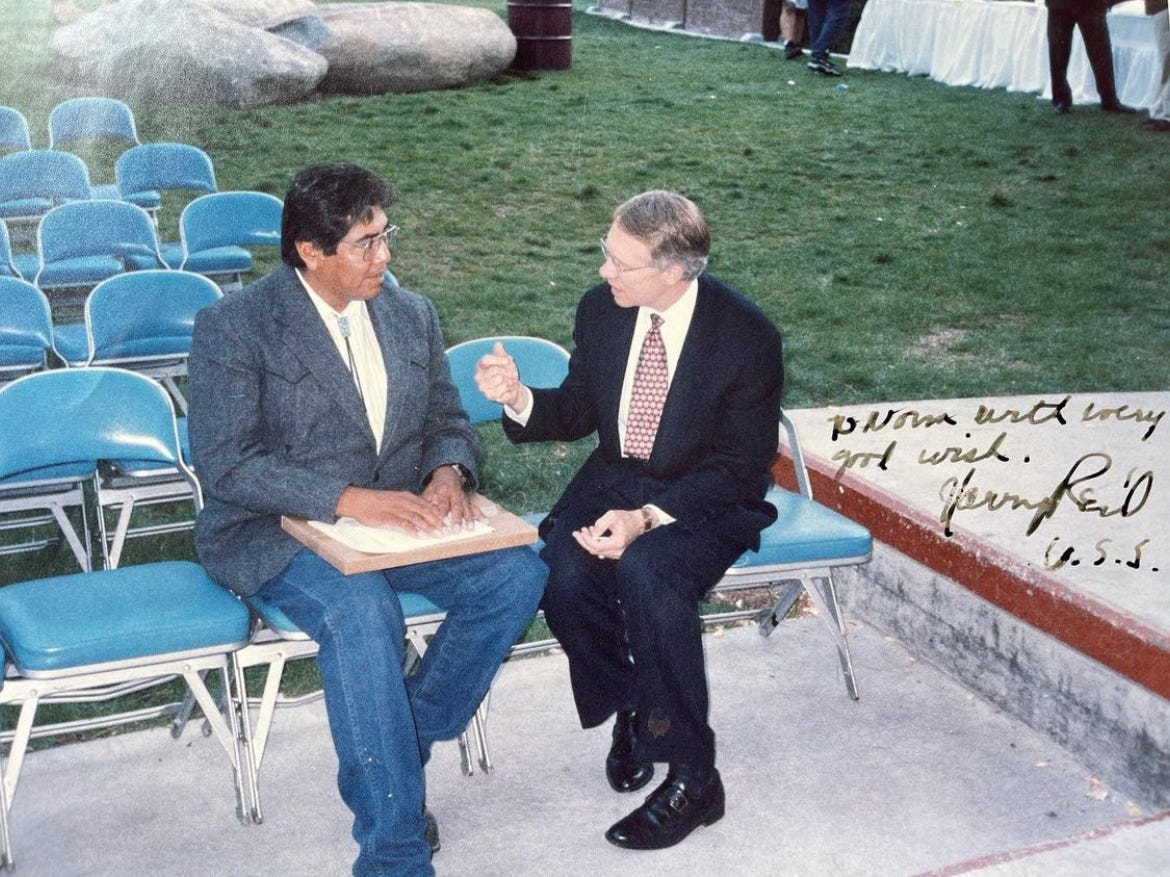

Remembering Harry Reid’s Native American legacy

‘I was able to do more for Nevada Native Americans than all the rest of the congressional delegations before me,’ the senator told me this past summer.

WASHINGTON – Former U.S. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid once visited with a group of tribal leaders who were gathered in his office for a meeting. He went around, one by one, asking each leader to state his or her tribe and af…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Indigenous Wire to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.